Last April, the Europeana conference, held during the Swedish Presidency of the Council of the EU, centered around the exploration of 3D technology and its role in digital cultural heritage. The conference aimed to delve into the reasons behind adopting 3D, while discussing its integration into the common European data space for cultural heritage and the overall digital transformation of the sector.

Historical 3D plays a pivotal role in the Amsterdam Time Machine project, which seeks to connect various digital sources that encompass the city’s rich past. This is achieved through the integration of these sources into a future shared infrastructure called the Amsterdam Data Hub (working title). Our objective is to employ 3D models as a gateway to historical data, combining visually captivating representations with information about residents’ occupations, dwelling locations, and their way of life during different eras. During the Europeana conference, our project manager, Boudewijn Koopmans, explored several avenues for utilizing 3D in digital cultural heritage.

What resources are available to us? In a previous pilot project called Living with Water, we collaborated with 3D Amsterdam, incorporating historical data and maps into their 3D rendition of Amsterdam. The significant advantage of this digital twin lies in its citywide coverage, with each building relying on the Basic Registration Addresses and Buildings (BAG) database, providing extensive information about each structure. However, it does not (yet) offer insight into how Amsterdam appeared in, for example, the years 1830 or 1748.

Another valuable source of 3D models comes from individuals who possess a passion for their cities. In Amsterdam, for instance, there is a wealth of citizen-created models portraying famous landmarks such as the Royal Palace Amsterdam, the Hendrik the Keyser stock exchange, and sections of the Jewish quarter, including the Waterlooplein. At the University of Amsterdam, students of the course De digitale stad / The Digital City learn to use software tools like Blender to recreate buildings based on blueprints, historical images, and other archival sources. Involving more students could be an intriguing direction for future projects.

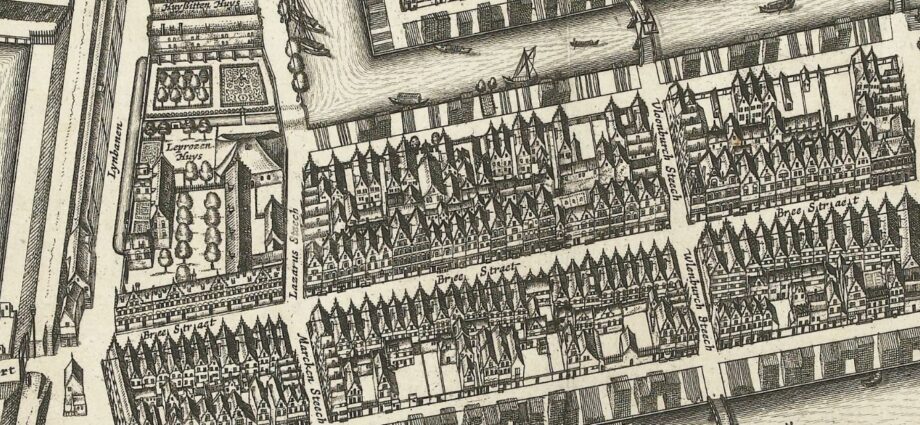

In conjunction with our pilot in the Jewish Quarter, our colleagues at the 4D Research Lab have created highly detailed visualizations of Vlooienburg, a demolished part of Amsterdam’s city center. This endeavor relied on a thorough study of diverse source materials. To explore alternative options due to time and resource constraints, the ATM is also investigating the utilization of software such as ArcGIS City Engine to generate 3D models of streets and buildings. Although less detailed, this approach still offers a compelling depiction of historical cities. Chiara Piccoli of the 4D Research Lab has already tested City Engine on 16th-century Amsterdam, and the technique is now being applied to previously unvisualized streets in the Jewish quarter.

The methodology employed encompasses a combination of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and procedural 3D modeling. The starting point is the HisGIS dataset, which represents digitized house plots from the 1832 cadastrial map. The GIS vector layer is modified to reflect the situations in 1625 (van Berckenrode’s map) and 1876 (Loman’s map). This modified GIS layer is imported into the procedural modeling software CityEngine, where a set of Computer Generated Architecture (CGA) rule files is written to describe the geometric properties of the buildings. The aim is to create a 3D layer that represents the houses along the streets, serving as an entry point for exploring the extensive dataset concerning the people who resided in them. The initial stage focuses on generating a grayscale 3D model of individual houses. In subsequent stages, this “backdrop” can be enhanced with more detailed reconstructions of individual buildings, based on available sources. The GIS layer of house outlines, prepared in the initial stage, can be progressively enriched with additional data in the attribute table, serving as a database and a foundation for future, more intricate modeling endeavors.

In conclusion, the Amsterdam Time Machine project aims to establish a distributed and shared infrastructure, consolidating all relevant data into a comprehensive knowledge graph. This unified platform will facilitate the development of applications that utilize the vast amount of historical data, including oral history projects. 3D models not only serve as crucial data sources but also offer a means to immerse the public in shared histories. The Amsterdam Time Machine project is enthusiastic about collaborating with partners such as the Time Machine Organization, Europeana, and numerous local entities in Amsterdam to breathe life into the past through an added dimension. Additionally, we are exploring opportunities to deliver 3D content to CARARE/Europeana in collaboration with other partners from the Local Time Machines (LTMs) ecosystem.

June 2023, Boudewijn Koopmans

2023-06-28