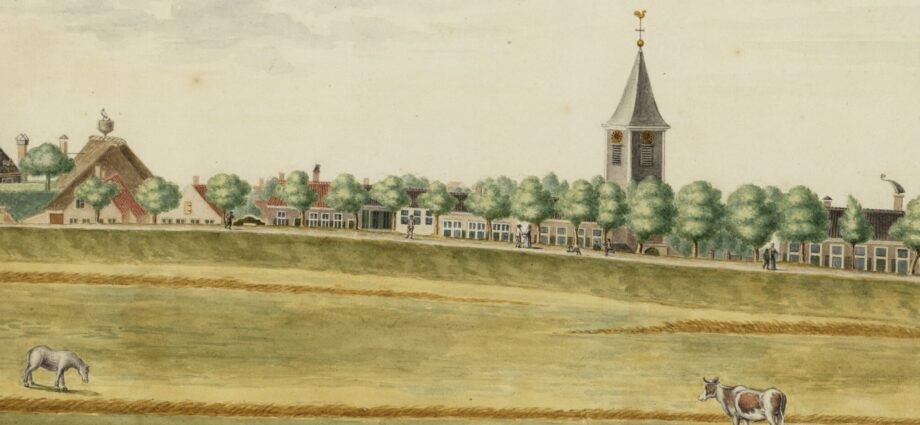

Today, ‘Sloterdijk’ is primarily used by many Amsterdammers as an abbreviation for ‘Station Amsterdam Sloterdijk.’ However, the history of Sloterdijk goes back many ages before the existence of the station. Sloterdijk originated in the Middle Ages along the Spaarndammerdijk, a dyke that protected the rural hinterland against the yet untamed wild waters of the IJ. Situated between the cities of Amsterdam and Haarlem, Sloterdijk was an important town, well-connected by the road on the dyke, and later by the Haarlemmertrekvaart (the current Haarlemmervaart), which was dug in 1631. The first train connection of the Netherlands, also from Amsterdam to Haarlem, commenced in 1839, of which the tracks also ran by Sloterdijk. Through the ages, the village held its own character and community. In 1921, Amsterdam annexed the municipality of Sloten, of which Sloterdijk was a part. The twentieth century marked a moment of big changes for Sloterdijk. While it had long been a small independent village amidst the rural surroundings, Amsterdam came knocking on Sloterdijk’s door. Sloterdijk’s history is a story about the battle for space, about priorities in urban development and about the worth of cultural heritage vis-à-vis industrial advancement. The age-old question of what must make way for what is yet again relevant, since the city of Amsterdam is changing the character of Sloterdijk again. Sloterdijk is part of the large urban development plan of Haven-Stad, in which housing is preferred over industry. Seventy years ago, it was exactly the other way around. We can identify three different moments when it comes to the battle for space, with the old village of Sloterdijk paying the price. How can we analyze these moments and how can we preserve the cultural value of Sloterdijk, with the help of digital methods?

1. The Western Garden Cities instead of farms and farmland

With the annexation of Sloten and the surrounding municipalities and hamlets, the city of Amsterdam acquired much-needed land. The city had burst at the seams. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the living conditions for many people in the center of Amsterdam were poor. People lived crowded together in poorly maintained homes and shanties, some of which collapsed. Modern homes needed to be built. After Plan Zuid and Plan West, the General Expansion Plan of 1935, which embraced the garden city concept, followed. Urban planner Cornelis van Eesteren was the mastermind behind this plan, which included the construction of five so-called garden cities: Slotermeer, Slotervaart, Overtoomse Veld, Geuzenveld, and Osdorp, with an artificial lake in between: the Sloterplas. The implementation of the plan did not begin until after 1945. Until then, Sloterdijk lay as a rural village under the shadow of Amsterdam amid the farmlands. To realize the construction of the western garden cities, the farmers had to be bought out, and the farms had to be demolished. The statue ‘De verdwenen boer’ (The Disappeared Farmer) by Karel Gomes now stands on the Molenwerf at the edge of Sloterdijk in memory of these people and their way of life.

Stadsarchief Amsterdam: Rural Sloterdijk in the 18th century

2. Train Station ‘Amsterdam Sloterdijk’ instead of an old village center

Sloterdijk is strategically located in terms of infrastructure. Until the eighteenth century, the Spaarndammerdijk was the main connection between Amsterdam and Haarlem, and afterwards, the Haarlemmertrekvaart. In line with the General Expansion Plan, Amsterdam decided in the 1950s that a station was needed to serve the residents of the western garden cities, precisely on the site of the village of Sloterdijk. It was located right next to the railway line that had previously already split the village in two. On June 3, 1956, the new station was opened: Station Amsterdam Sloterdijk. This is not the station we know today; it was located several hundred meters southeast of the current station. To build the station building, a large part of the village was demolished. The station building had a temporary purpose but still served for 29 years before eventually being demolished. Meanwhile, the new, modern Sloterdijk station had been built and put into operation.

Stadsarchief Amsterdam: Construction of the old station Sloterdijk with the St. Peter’s Church in the background.

3. The A10 Ring West and businesses instead of what remained of the village

The second major progress project that presented itself and for which the old village had to make way was the construction of the highway Ring West. For this purpose, a viaduct was built over the railway line to Haarlem. The A10 and the route of the Coentunnel would run through Sloterdijk. This meant that an even larger part of Sloterdijk had to be demolished. All the houses on one side of the Dorpsstraat were torn down. Around the A10, various tall office towers were built, as part of Westpoort, the business park of the Westelijk Havengebied. Today, this area houses, among others, the Tax Office and the UWV. The original access road, with the bridge over the Haarlemmertrekvaart and the ‘Sloterdijkschool,’ had to give way.

Stadsarchief Amsterdam: Construction of the A10.

What remains today is the St. Peter’s Church and a handful of houses along the old Spaarndammerdijk. If one walks through the street, overlooking the church and the graveyard, the contrast with the tall glass and concrete buildings around it is astonishing. Because of decisions that have been made in the past, a village with great cultural value has been largely lost. However, there are ways to digitally reconstruct Sloterdijk and its various stages of development and destruction. One way is to take old maps of the area and georeference them. In this process, a few reference points on the map are taken and laid over the modern map to situate it in space. This is an insightful method to visualize the spatial-geographic changes throughout the centuries. Another method is to construct a historical 3D environment of the village, in which all the demolished buildings are visualized. Photographs can be used to place on the facades of the models, so that visitors can imagine the viewpoint of a certain reference point within the modeled area. We are currently working out the various methods, to be able to integrate Sloterdijk in the Amsterdam Time Machine. We will post on any relevant updates on our website.

By Nynke Anna van der Mark, September 2023.