Amsterdam, a rapidly expanding city, is confronted with a pressing housing shortage, further compounded by the challenges posed by climate change. This necessitates the task of formulating a sustainable urban future to accommodate the growing number of residents. The most prominent manifestation of this challenge is observed in the Haven-Stad plan area, situated in the north-west of the city, predominantly occupied by the Port of Amsterdam and industrial complexes. Over the coming decades, this area is slated to accommodate approximately 70,000 residential units and generate 58,000 job opportunities. An essential focus of this project is the transition from conventional fossil fuels to sustainable and renewable energy sources. Interestingly, Haven-Stad encompasses an existing historical example of an early energy transition, exemplified by the Westergasfabriek, a former gas factory turned cultural site. Located in the vibrant Westerpark, one of the twelve sub-areas of Haven-Stad, the Westergasfabriek is renowned among Amsterdam residents as a venue for festivals and recreational activities during weekends. The park encompasses several well-preserved structures that house a cinema, restaurants, art exhibitions, and a multitude of other offerings. The transformation of the Westergasfabriek into a cultural hotspot exemplifies the successful conversion of industrial urban heritage into a thriving urban center. The Westergasfabriek serves as a sub-project within the larger pilot project of Haven-Stad, currently under the research purview of Nynke Anna van der Mark. The collaborative efforts of this endeavor also involve Transition Scapes, a research project undertaken by the Civic Interaction Design Research Group at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences.

Historical Context

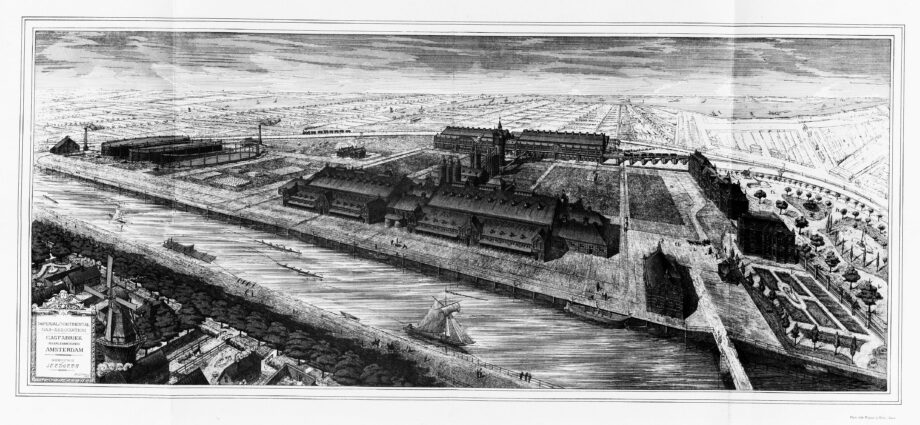

In 1883, the city of Amsterdam granted a concession to the British Imperial Continental Gas Association (ICGA) to establish a coal gas plant in the western part of the city. This gas factory was positioned in the former Overbraker Binnenpolder, situated between the prominent waterway connecting Amsterdam and Haarlem, known as the Haarlemmertrekvaart, and the newly constructed railway tracks linking the two cities. The design of the gas factory’s numerous structures was entrusted to architect Isaac Gosschalk, and construction commenced in 1883. Subsequently, in 1889, the city of Amsterdam assumed control of the gas factory’s operations from the British company. The primary purpose of this facility was to produce gas for street lighting throughout the city, as well as for domestic use in households.

However, in 1918, the establishment of Koninklijke Nederlandsche Hoogovens en Staalfabrieken NV (Hoogovens), a steel and aluminum company known today as Tata Steel, disrupted the gas production landscape. This factory operated blast furnaces that generated oven coke gas, a byproduct that led the Westergasfabriek to shift away from coal gas and instead produce water gas. Furthermore, in 1959, the Netherlands discovered a substantial underground gas field in the northern region of the country, known as the Groningerveld. This development rendered the gas factory in Amsterdam obsolete. Finally, on 28 March 1967, gas production at the Westergasfabriek ceased. The surrounding soil and underground areas of the gas factory were heavily contaminated, featuring various toxic substances, including cyanide, making it as a classic brownfield location. Following the closure of the factory, the municipal energy company, Gemeentelijk Energie Bedrijf (GEB), utilized the terrain, primarily for storage purposes. While some structures were demolished, many achieved a monumental status shortly thereafter.

In 1993, the city made the decision to allocate the former gas factory site for cultural activities, initially for a one-year period, which was later extended to seven years. This arrangement allowed a diverse range of cultural entities to lease spaces within the premises. However, starting from the year 2000, all public activities were temporarily suspended as the city authorities determined that the soil required thorough decontamination to remove the lingering toxins buried beneath. Concurrently, the factory site was expanded to include its surroundings, resulting in the creation of a sizable park known as the Westerpark. Renowned landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson was responsible for the park’s design.

3D-Visualiations and Linked Open Data applied to the Westergasfabriek

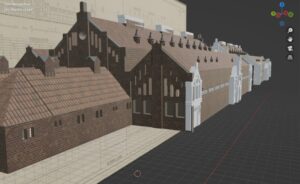

We are currently working on visualizing and mapping the late nineteenth-century Westergasfabriek. Our efforts encompass a variety of methods and techniques. One notable aspect involves the creation of 3D models of the Westergasfabriek buildings by PhD-fellow Francesca Fabbri, affiliated with the University of Bologna. (See this blog post by Boudewijn Koopmans about the Significance of 3D) These models serve a dual purpose: they offer accessible visual representations of a bygone era, while also serving as repositories and gateways to historical data. One of the key advantages of these digital 3D models is their capacity to incorporate historical photographs, sourced from the City Archives. By integrating these images spatially, a new dimension is added to the archival materials. Additionally, we are consolidating various sources of information into comprehensive datasets, with a specific focus on buildings and individuals associated with the Westergasfabriek. An example is the inclusion of unique historical resources, such as staff photos annotated with last names, which allows them for cross-referencing against the city’s public retirement administration records. Through this process, it becomes possible to extract first names and, in some cases, birth dates. Furthermore, these records can be cross-checked against other sources of public administration preserved by the City Archives.

As a result, an ever-expanding collection of data is being amassed and amalgamated. This data is subjected to cleaning and standardization procedures, in accordance with the vocabulary defined by Schema.org. The structured data that emerges from this process holds immense potential, as it can be made available as linked open data. This wealth of information can be harnessed to develop public applications, such as an augmented reality experience, which visitors to the Westergasfabriek can utilize to delve into the area’s historical past. Moreover, this data serves as a valuable repository for city administrators and researchers, shedding light on the early days of an energy hub and subsequent transitions. This narrative holds significant importance, as it underscores the timeless nature of challenges related to energy supply and the conversion of industrial sites into cultural heritage. By drawing from the past, both the city and its inhabitants can gain insights into how these challenges have manifested in prior eras. Thus, this project not only fosters an appreciation of history but also offers invaluable guidance for the present and future.

Nynke Anna van der Mark, June 2023

As a result, an ever-expanding collection of data is being amassed and amalgamated. This data is subjected to cleaning and standardization procedures, in accordance with the vocabulary defined by Schema.org. The structured data that emerges from this process holds immense potential, as it can be made available as linked open data. This wealth of information can be harnessed to develop public applications, such as an augmented reality experience, which visitors to the Westergasfabriek can utilize to delve into the area’s historical past. Moreover, this data serves as a valuable repository for city administrators and researchers, shedding light on the early days of an energy hub and subsequent transitions. This narrative holds significant importance, as it underscores the timeless nature of challenges related to energy supply and the conversion of industrial sites into cultural heritage. By drawing from the past, both the city and its inhabitants can gain insights into how these challenges have manifested in prior eras. Thus, this project not only fosters an appreciation of history but also offers invaluable guidance for the present and future.

Nynke Anna van der Mark, June 2023

As a result, an ever-expanding collection of data is being amassed and amalgamated. This data is subjected to cleaning and standardization procedures, in accordance with the vocabulary defined by Schema.org. The structured data that emerges from this process holds immense potential, as it can be made available as linked open data. This wealth of information can be harnessed to develop public applications, such as an augmented reality experience, which visitors to the Westergasfabriek can utilize to delve into the area’s historical past. Moreover, this data serves as a valuable repository for city administrators and researchers, shedding light on the early days of an energy hub and subsequent transitions. This narrative holds significant importance, as it underscores the timeless nature of challenges related to energy supply and the conversion of industrial sites into cultural heritage. By drawing from the past, both the city and its inhabitants can gain insights into how these challenges have manifested in prior eras. Thus, this project not only fosters an appreciation of history but also offers invaluable guidance for the present and future.

Nynke Anna van der Mark, June 2023

As a result, an ever-expanding collection of data is being amassed and amalgamated. This data is subjected to cleaning and standardization procedures, in accordance with the vocabulary defined by Schema.org. The structured data that emerges from this process holds immense potential, as it can be made available as linked open data. This wealth of information can be harnessed to develop public applications, such as an augmented reality experience, which visitors to the Westergasfabriek can utilize to delve into the area’s historical past. Moreover, this data serves as a valuable repository for city administrators and researchers, shedding light on the early days of an energy hub and subsequent transitions. This narrative holds significant importance, as it underscores the timeless nature of challenges related to energy supply and the conversion of industrial sites into cultural heritage. By drawing from the past, both the city and its inhabitants can gain insights into how these challenges have manifested in prior eras. Thus, this project not only fosters an appreciation of history but also offers invaluable guidance for the present and future.

Nynke Anna van der Mark, June 2023